The

C&D Canal at Chesapeake City - Early Forties (Part 2)

Bobby Hazel Jumps from the channel

marker in 1948

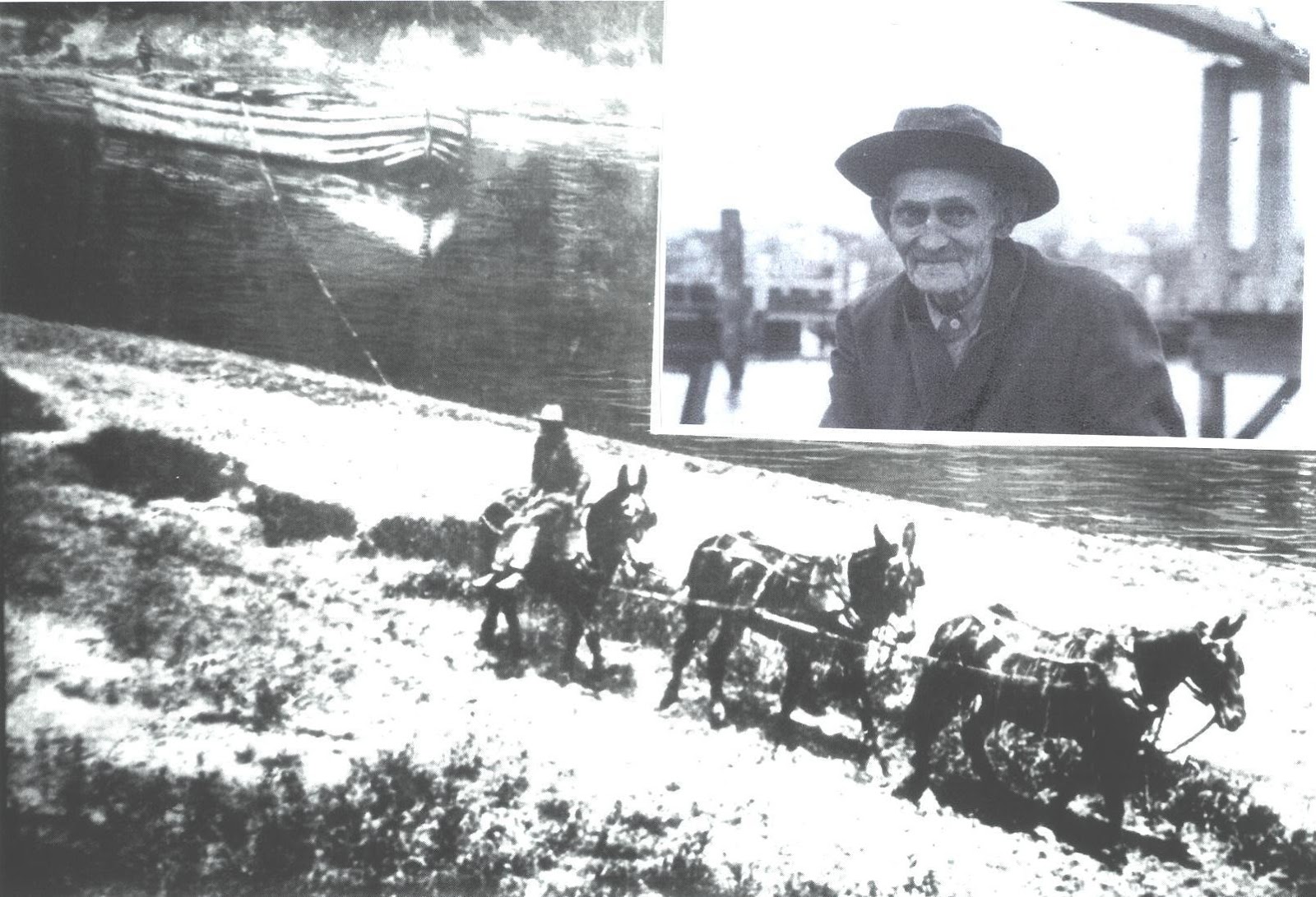

Mules on the Towpath - Inset: Harry

Borger, former muleskinner

I used to dive into the canal and swim all

around for hours. Sometimes I would swim across to Ticktown on the North Side;

I’d take my time and let the current carry me; I’d float a while on my side or

on my back; I’d try the breaststroke, then switch to the doggie paddle, but

usually end with the powerful side stroke, which worked best for me. I would

always end up far from where I had been on the other side, either east or west

depending on the direction of the current. Swimming was such a great joy for a

country boy with nothing to do on those long, lazy summer days. In those ancient

days of glory, I would sometimes hook school and spend the day fishing on a

barge in the Basin. And I think that when I die and go to heaven, when everyone

else is praying in a celestial church service, I’ll be lying in the sun on an

old rusty barge, reclined easily on my wings, trying to hook a nice catfish or

yellow Ned.

As a boy of seven or eight, I remember always

having an indescribable foreboding or sense of uneasiness in the back of my

mind because of all the talk about the war that was raging in Europe and in the

Pacific. But at that certain time, as I sat there on the grass next to the

Hole-in-the-Wall on that special evening, I recall vividly the feeling of comfort

I derived from the stillness and beauty of our canal. I peered out into it and

noticed that it had reached full high tide, for the water was almost touching

the cross boards on the crumbling granary. And yet the stillness on the proud

canal was eerie. The contrast of light and dark images spread out against the

silent waters made me feel a little strange.

And then, from my right side, out of the

Basin, a small rowboat slid into view. It was powered by an old, old man whose

rowing skills were so good that I could hear only a slight, dull thump of the

oars rolling in their oarlocks. The skiff was small and the man, whose face was

dark and wrinkled, was rowing in the forward-facing method, the ancient method,

which I had never seen before or since. His strokes were effortless. As he

passed in front of me, the oars feathered the still water, hardly breaking the

surface as man and boat, centaur at sea, glided past at a surprising pace.

After it passed, its gauzy wake was barely visible on the water, a brief

remnant of an essence that is with me still. Soon small, silent ripples made

their way to the sandy beach, nudging ever so gently the thin strands of sea

grass next to the piling. I found out later that the rower was Harry Borger

who, in his youth, had walked the tow path as he led the mules that pulled the

barges through the narrow canal.

Did you ever watch as darkness descends on

the water? It’s an odd sensation if you catch it just right. As I sat there

alone, waiting for my father to pick me up, the current had started moving slowly

the other way, and the moonlight, pinch hitting for the sun, illuminated the

surface, giving the colossal, living body of water an enchanting, silver glow.

The vast giant was on the move again; the world was in motion, breathing once

again. With all the uncertainties of those war-plagued, furious Forties, at

that special time I felt that everything was going to be all right.

No comments:

Post a Comment