Carnival Days—Chesapeake City’s Firemen’s

Carnivals in the Forties

Advertisement poster, circa

1948

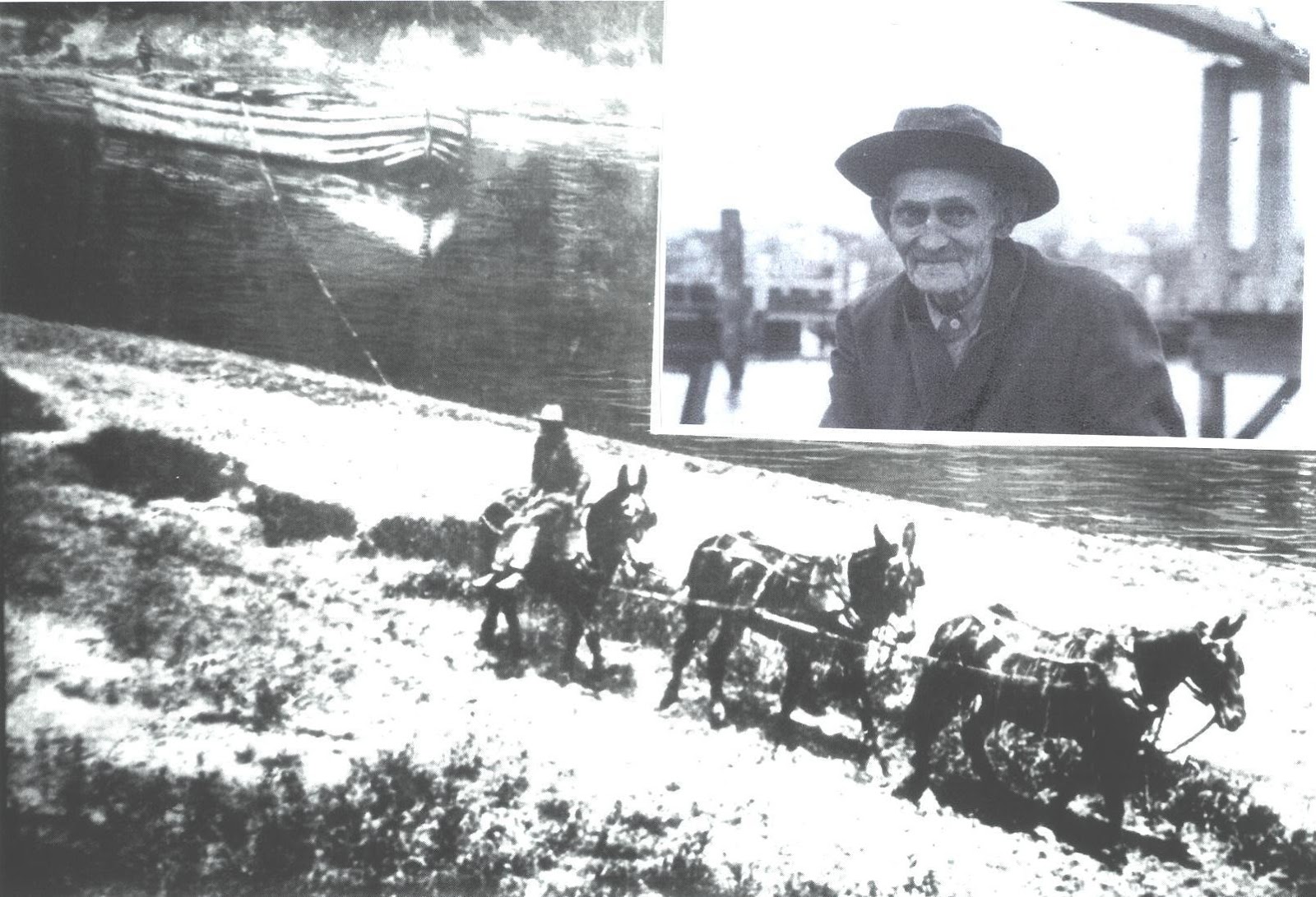

Carnival grounds, setup for

Reynolds’ Rides, circa 1956

A

major event that I looked forward to as a boy was the firemen’s carnival held

each summer next to the firehouse on Chesapeake City’s North Side. My earliest

memory of the carnival is standing with my mother at a long, narrow counter and

listening to the clattering of a high vertical dice wheel as it was being spun

by an attendant. Mom gave me a nickel to place on a number, and I said, “Which

number should I put it on?” The counter had numbered blanks that corresponded

to the numbers circling the wheel. Mom thought for a moment and said, “Well,

why don’t you play 25—your birthday number?” I did and, sure enough, that’s

where it landed and I won a prize. That was 60 years ago, the last time I ever

won anything.

But,

win or lose, our carnival was a joy. Later, as an early teenager, I’d walk

across the bridge and across the Sisters’ field to attend. The carnival was set

up around the sides and back of the early firehouse on Lock Street. The various

activities—games of chance, food concessions, and the unique Reynolds’

Rides—were interspersed throughout the grounds. These rides were unique because

Harold Reynolds, Sr. designed and build them out of materials he salvaged from

the area junk yards. I have a vague memory of the rides—black steel

contraptions—powered by motors with dark, rumbling, well-lubricated gears and

chains. Mr. Reynolds and his son, Bud, had to grease the gears frequently and,

occasionally, a ride would break down so that the children would have to wait

in line until Mr. Reynolds climbed up into the works to fix the problem.

Many other people, who were

children or young adults in the late forties, remember Chesapeake City’s

exceptional firemen’s carnivals. Mary

Brown, Mr. Reynolds’ daughter (now deceased), who worked at the carnivals,

remembered: “My father made all kinds of rides for the firemen's carnival. He

built several kiddy rides—a train, a merry-go-round, a Ferris wheel, and other

rides, as well as some of the stands that were used at the carnival. Daddy

carved the merry-go-round horses, and the pattern that he used is now owned by

my brother.

“He also built the trailers

that were needed to haul all the things from one place to another. I used to

work at the carnivals sometimes. We popped popcorn and sold cotton candy and

snowballs all night long. And then we'd get up the next day and start all over

again.”

Lewis Collins has clear memories: “Miss

Nell Borger used to run the penny wheel. You put your penny down to try to win

five pounds of sugar or a box of oatmeal. Paul Stapp and I worked the carnival

glass stand. All the dishes would be sitting in the stand and people would lean

over the rail and try to pitch a nickel into one, and if it stayed they got the

dish. Carnival glass is very collectible today. There was also the Big 6 Wheel,

where you’d put your money on a number. The big wheel was the dice wheel that

made the click-click noise. Those wheels had to be well-balanced; I know that.

And there were always fireworks. If the carnival was held during the Fourth of

July week, the fireworks were on the Fourth. If not, they were held on the last

night of the carnival. They had the fireworks in the field behind the

firehouse.

“We really had big parades

in those days. Fire companies came from all over. On certain nights they would

cut the prices for the kiddy rides. Harold Reynolds made the rides, and he got

better at it as he went along. I’ll tell you, he was a craftsman. During the

war, when you couldn’t buy toys, he used to make them—wooden wheelbarrows,

wooden wagons, and others. He even made wooden wheels for them; that man could

do anything. My father sold the toys in his store on Biddle Street.

Chet

Borger

has vivid memories also: “Since my dad was a volunteer fireman and my mom and

older sister belonged to the Ladies Auxiliary, I would be given the task of

placing flyers and placards around town in the local businesses and on any

fixed object that I could reach. I was able to score some free tickets for the

rides. We also had a big parade

every year. Prizes were awarded for the companies traveling the farthest

distance, the vehicles with the most lights, the best bands, and the most

attractive units. Folks would cheer and shout as the fire engines drove slowly

by, with the men hanging off the sides and back. My Mom had made me a junior-sized

marching uniform to walk along with my dad. I remember that it consisted of a

white pair of pants with a matching jacket. The front was festooned with brass

buttons, and it was topped off with a matching white cap with a gold band

across the front. I was a handsome sight at the ripe old age of ten.

Joe Allen worked at the carnival and

recalls the distinctive rides: “Mr. Reynolds built all of those early rides.

The story is that he went to Wilmington to get a load of steel from a junk

yard. And the guy up there asked him what he was going to do with it. Mr.

Reynolds told him that he was going to build a Ferris wheel. “No, you’re not

going to build a Ferris wheel out of that junk,” the guy said. Well, Mr.

Reynolds went home, built a Ferris wheel, and sent a picture of it up to the

guy.”

Bud Reynolds, who lives on Chesapeake

City’s North Side and whose son is still in the carnival business, tells his

story: “I was 13 when I started working for my dad with the carnivals. We lived

on Canal Street, and that’s where he brought the raw materials to make the

rides. He constructed and assembled them in a vacant lot next to our house. We

got started right after the war, when you couldn’t get much of anything. My dad

and I were both in the fire company, and they wanted to put on a carnival but

couldn’t get anybody, so my father built a merry-go-round. He even carved the

wooden horses himself. That was his first ride.

“He could make anything he

set his mind to. He built all the rides from scratch, from junk yard iron and

steel. In 1948 he built a kiddy train with tracks. Next he built a Ferris

wheel, first a small one and then a larger one. On the first rides he made, he

used old truck rear-ends to power them. He made two revolving power swings that

way. Another swing he designed by using old airplane belly tanks. Each cab had

its own electric motor that spun a propeller to pull the airplane around. We

also had wooden ponies pulling their carts in a circle. The ride was up on a

platform. My father designed and constructed the whole thing.”

Yes, the firemen’s

carnivals of the forties and early fifties were magical events for me and many

others who were lucky enough to attend. One thing that made them special was

that they were run by real firemen and local townspeople whom we all knew. And,

for us in Chesapeake City, the carnivals were especially noteworthy because all

of the rides were made and operated by our own mechanical genius.